My granddaughter was at the house for a sleepover a few days ago. She’ll be three-years-old soon. Her parents have promoted a routine of a “story” at bedtime. You lie down with her on the bed and read or tell her a tale. In minutes, she’s asleep, usually. It’s a similar routine in many households. At her grandparent’s house, we’ve tried to keep that routine going. It’s not hard. And it’s never forgotten. The reason is simple: She reminds us.

“Tell me a story,” she insisted, smiling and pulling the covers up to her neck.

While I hung up the hand towel she had used from the bathroom and put away the toothpaste, I said, “Go pick out a book and we’ll read.”

There’s as stack of kids’ books in a basket in the downstairs family room especially for her. I assumed that’s where she would go to search out a favorite. Instead, she stood before a bookcase in the same room, surveying the spines of some fifty titles, the index finger on her right hand scanning the words and colors.

“This one,” she exclaimed.

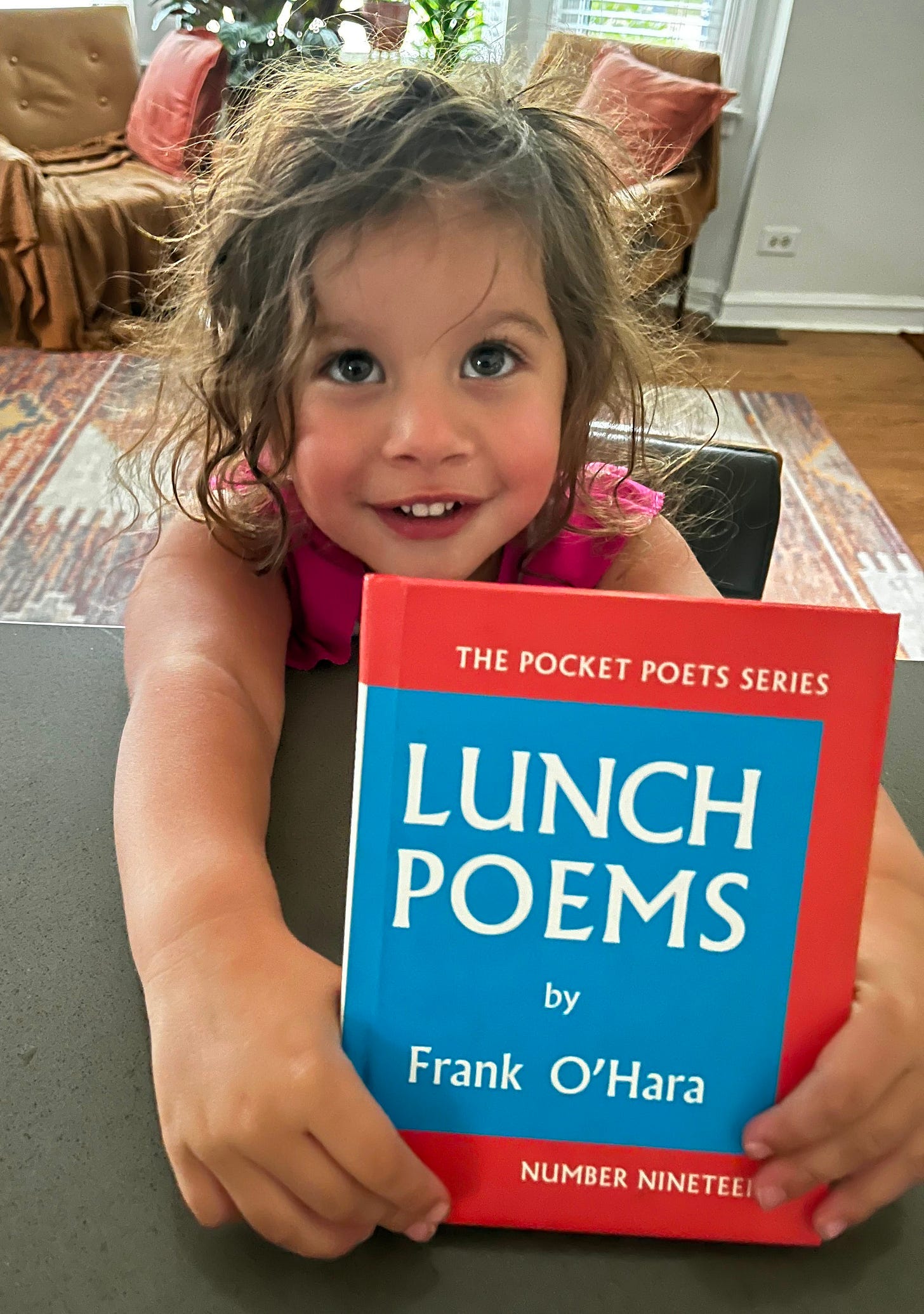

In her hand was Frank O’Hara’s classic Lunch Poems.

My immediate reaction was to say, “Oh, no, not that one, honey.”

Then I thought again. Why would I say that?

“You know what,” I said, smiling. “Let’s do it. Sure. Let’s read Frank O’Hara.”

I rested beside her on the bed, opened the book, and thought for a moment, Hmm, is there something here that might be highly inappropriate? Then, I dismissed that thought and glanced at the titles in the collection.

“‘Music’,” I said. The poem is a short one, good for a bedtime story.

O’Hara’s collection was published in 1964. It quickly became a cult classic. Each verse written during his “lunchtimes” while he worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He had been a clerk at the information and sales desk in the front lobby, and later became an assistant curator at the museum and an associate curator in 1965, all of this upward movement without formal training. He had an “eye” for art, and an “eye” for story. Sadly, though, he wasn’t around long. O’Hara died a strange death a few years after the publication of Lunch Poems, struck by a beach taxi on Fire Island and dying at the age of 40.

One formal analysis of O’Hara’s “Music” claims it “explores the transformative power of music, its ability to transport us beyond the mundane and into the realm of the sublime. The poem's imagery evokes a sense of euphoria, ecstasy, and transcendence.” O’Hara had used music as a metaphor for life, its power to move us, and like life, how it can be a wonderful and transformative experience.

And so, I began to read, trying to scan ahead for anything that might be inappropriate. I had read the poem before, but possessed an uncertain memory. I also knew that much of what was there for an almost three-year-old would certainly be beyond her comprehension. And so I keep reading. Line after line.

It took no more than a minute or two. And when I finished, I looked into my granddaughter’s sleepy eyes.

“Did you like that?” I asked.

I could see her thinking, contemplating.

“Why are the dogs in blankets?” she asked.

The line from O’Hara’s poem is “I shall see my daydreams walking by with dogs in blankets.”

“Well,” I said, pausing with no real answer to give, scrambling internally to give some vague meaning to the metaphor O’Hara was using. “Sometimes,” I said, still searching, “dogs like to sleep under blankets, you know, like people.”

“They do?” she asked, her eyelids heavy.

“Yeah. Like you right now, under the covers.”

I could see her thinking. After a moment, she asked, “Can we read more?”

I turned the page and found the poem “On Rachmaninoff’s Birthday.”

“Let’s read this,” I said, repeating the poem’s title out loud.

“It’s his birthday?” she asked.

“Yes, I guess so.”

“Like mine,” she said. “Like my birthday, soon.”

“Yes, like yours. And how old will you be?”

“Four,” she said.

Don’t rush it, girl, I thought.

“Try again,” I said. “How about three?”

“Ok. Three.”

I held up three fingers and she counted them off. “One, two, three.” I smiled. “Are you ready for this poem?”

She nodded.

Two lines in, I heard her breathing shift. Deeper, almost a child’s snore. Her eyes were now closed, her head heavy on the pillowcase. I touched her hair and kissed her arm.

Nothing against Goodnight Moon or any of those wonderful Dr. Seuss books, but this time it was Frank O’Hara, the iconic New York poet that my granddaughter chose as the one who would soothe her into her dreams.

David W. Berner is the author of several books of award-winning fiction and memoir. His latest, Daylight Saving Time is available now. His novella, American Moon will be published by Regal House Publishing in 2026.

Delightful. What you and your granddaughter shared through serendipity, I experienced every day from earliest chilldhood. My parents taught poetry, recited it from memory and poured it over my head, trusting me to be enchanted. I didn’t have to understand the words to feel the mood and the music.

Wonderful story. I love how you trusted her and her choice, then trusted your own bravest thought, and together you let life just flow along.