We missed the perfect tree-planting day by forty-eight hours. Arbor Day came two days before, which would have been the optimal day to do this work. Instead, there I was, on a Sunday morning, moving a balled and potted dwarf river birch, a shrub-like tree to the spot in our humble garden where my wife was pointing her very green finger.

“I like it there,” my wife said. “No, wait. Maybe back a bit more.”

Missing Arbor Day for a tree planting was no big deal in the overall scope of things, but it would have been nice—symbolic, even.

“Hmm,” she wondered. “Let me go stand in the backyard to see how it looks from there.”

It was going to be the tree’s permanent home. It needed to be just right.

From all angles, it looked great. And so, there it would be planted in the ground. Not that day, but soon. This would be its home, roots spreading in the notoriously damp soil of this section of the garden.

That afternoon, I read a wonderful post online from Poetic Outlaws about the “Lawrence Tree,” the magnificent ponderosa pine outside the former humble home of D. H. Lawrence in Taos, New Mexico. The same tree that Georgia O’Keeffe painted when she came to visit the Lawrence Ranch. The unique and stunning perspective was captured by lying down on the bench near the tree and looking into the night sky.

Lawrence was intensely connected to nature, and particularly trees. He found grounding in the natural world, and wrote often about his experiences there. He saw trees as symbols of the human condition.

I never knew how soothing trees are-many trees and patches of open sunlight, and tree presences; it is almost like having another being. — D.H. Lawrence

Trees have always been a kind of inspiration. The apple tree of my childhood home, the one I climbed often and from which I frequently ate its green fruit. The giant black cherry tree in the family backyard with its massive gnarled trunk. The towering pines of the Pennsylvania forests where I walked with my boyhood dog. My wedding ring is made from the desert ironwood tree, a Native American symbol of “binding together.” And the great magnolia that stands outside our home’s back door has been a canopy for celebrations, under which we have shared wine and food and love. Our neighborhood street is lined with old-growth maples and oaks, and every time one is diseased or damaged by the wrath of the modern world and must be felled, a part of me cries.

Trees have always been a part of literature, too. There’s the fictional Tumtum Tree in the poem “Jabberwocky” from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass. And of course, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and certainly Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree. There’s a wonderful memoir, Under the Birch Tree by my fellow author, Nancy Chadwick. One of my favorite trees is in Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. Buddha meditates for 49 days and eventually attains enlightenment under a bodhi tree. Trees are all over the literature of the ancient Greeks and Romans. And trees in poetry are as thick as a forest, including Robert Frost’s "The Sound of the Trees,” an exploration of the struggle between longing and rootedness symbolized through tree branches swaying in the wind.

Years ago, when I had the honor to live and work in the Florida cottage where Jack Kerouac wrote The Dharma Bums, I frequently sat on the back door stoop not far from an orange tree (or was it tangerine?) that had been on the property as long as anyone could remember. Jack had done the same, even collecting fruit in a basket. And although I don’t believe Kerouac ever wrote about that particular tree, trees frequently appeared in his writing.

One afternoon as I just gazed at the topmost branches of those immensely tall trees I began to notice that the uppermost twigs and leaves were lyrical happy dancers glad that they had been apportioned the top, with all that rumbling experience of the whole tree swaying beneath them making their dance, their every jiggle, a huge and communal and mysterious necessity dance, and so just floating up there in the void dancing the meaning of the tree. I noticed how the leaves almost looked human the way they bowed and then leaped up and then swayed lyrically side to side. —Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums

Also at the Kerouac House is the tree Jack named “Grandfather,” a gigantic live oak, moss and all, that looms over the front of the property. The 250-year-old tree sustained big storm damage a few years ago, but at last word, it’s still displaying its grandeur.

And with all the trees in my life, I must remember the image that hangs over my desk in the writing shed. The whimsical work of my stepdaughter, reminding me how fanciful the tree can be.

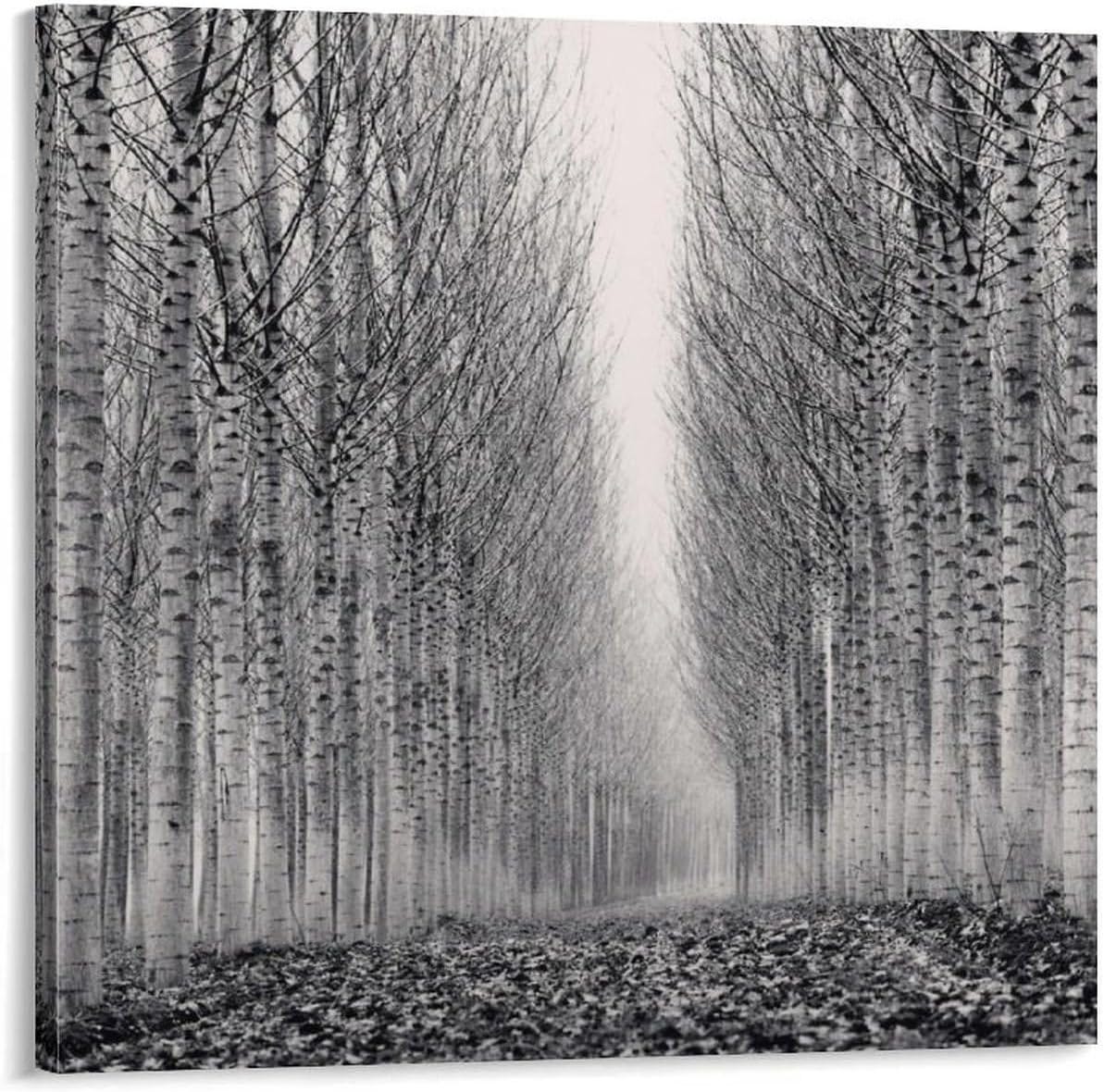

And lastly. how could I not mention the tree’s presence in great photography.

I recently learned of Michael Kenna, renowned for his black and white photos of trees. He uses incredibly long exposure times, as long as ten hours, and works in the wonderful light of early morning or just before dusk. Clearly Kenna is in love with the tree.

And so am I, especially our newest.

In a day or two, I’ll dig the hole and my wife will fill it with good soil and water its roots, and we’ll watch it grow, giving it and us a new beginning, as Celtic mythology claims. And as Native American wisdom reminds us, the river birch, in all its forms is the symbol of one who never stops wondering, of our childlike innocence, our inner resolve to explore far beyond the confines of the ordinary, igniting the imagination.

The tree as muse.

David W. Berner is the author of several books of award-winning fiction and memoir. His latest, Daylight Saving Time: The power of growing older is available now. His debut poetry collection, Garden Tools is due out in October 2025 from Finishing Line Press. His novella, American Moon will be published by Regal House Publishing in 2026.

While I am enjoying my young apple tree in bloom, getting trees started in the high desert is a labor of love. I hope I live here long enough to see some share their canopy. Trees outlive us and offer perspective on time! Good luck with your new member of the outdoor family

Wandering is my jam too. Cheers to trees