I’m sitting in the dark in the early morning. Only a small reading light nearby. Rain touches the window. In my hand is a new copy of Siddhartha, Herman Hesse’s classic. It’s a collector’s edition—a stunning artistic cover with folded flaps for marking your place, its matte finish silky and comfortable in the hand. I read this story a long time ago, and then again years before this morning’s reading. Now, in my 65th year, Hesse’s lyrical novel of a quest for knowledge and meaning has something new to say to me, or something that only now is revealed. This new reading comes after a significant passage of time, a place in my own journey that I and few others could have predicted. Yet, it is familiar to many who have come to this marker in time.

In the Introduction to this edition of the novel, I am reminded that the word siddhartha is made up of two words in Sankrit—siddha and artha. Together they mean “he who has found meaning.” I wonder if this is what it has come to—this passage of time, the discovery of meaning, at least a meaning at some level of human capacity. It’s been said that Hesse’s great story reveals to the reader that time is an illusion, and although the meaning of our thoughts and words as we move through the chapters of a life may sometimes appear unclear, one hopes to look at each stage of a life with wonder. This is where I find myself on this morning, in the final chapters of both a masterpiece and a life, and in wonderment.

Some have called it Boomer Power. That seems a bit boastful, even silly. Still, there may be something to it—the creative juices still running through old veins. Time, as Hesse implies in his book, is only an illusion and not a time to turn off the faucets. It seems more likely that it’s time to open up those pipes all the way.

Why is this?

A friend suggested that the older we are the more experiences we have to draw on. There is certainly truth in that. In Siddhartha, the reader learns that experience is everything. It leads to understanding and that leads to creativity. I would add that as we age, we often learn that there are no true answers to anything, maybe more questions. And that, also, leads to creativity. Question and you will find yourself overwhelmed with what the artist might label as inspiration.

Research shows that artists—poets, painters, musicians, and novelists—who have clear and immediate goals, work in a particular kind of timeframe. There’s evidence that their most creative period is more a product of the type of creator they are and the nature of your work. But research says many find the most creative work comes when they are older, even far past middle age.

There’s evidence that sensitive and reflective older people have developed an eye for the ambiguity or tragedy inherent in life’s important themes—love, hate, life, death, despair, pleasure, pain, freedom—each having no clear or simple meaning to the older person. In the early 1990s, a traveling exhibition entitled Still Working came to dozens of museums worldwide. It featured more than 30 obscure lifetime artists over the age of 60, some of them engaged in the strongest work of their careers, not settling, not looking over their shoulders, all demonstrating what had been labeled a “brightening of spirit and a renewed outburst of invention.” Maybe it’s about earning the right to not give a damn what anyone thinks and simply to create for the sake of creation.

Paul Cézanne collapsed during a rainstorm while painting outdoors. He rallied over the next few days to finish the portrait, adding some small brushes of color while bedridden. He died in the early morning at the age of 67.

Poet Wallace Stevens did most of his work after the age of 50.

Angela’s Ashes was published in 1996. Frank McCourt was 66.

Annie Proulx was 58 when her novel The Shipping News won the Pulitzer Prize 1993.

Dylan is 80. A Nobel Prize winner. Still writing.

David Crosby is 80. He has a new album.

John Prine was 73 when he died, writing songs until the end.

Paul McCartney is 79.

Tony Bennet died at 95, singing until the last breath.

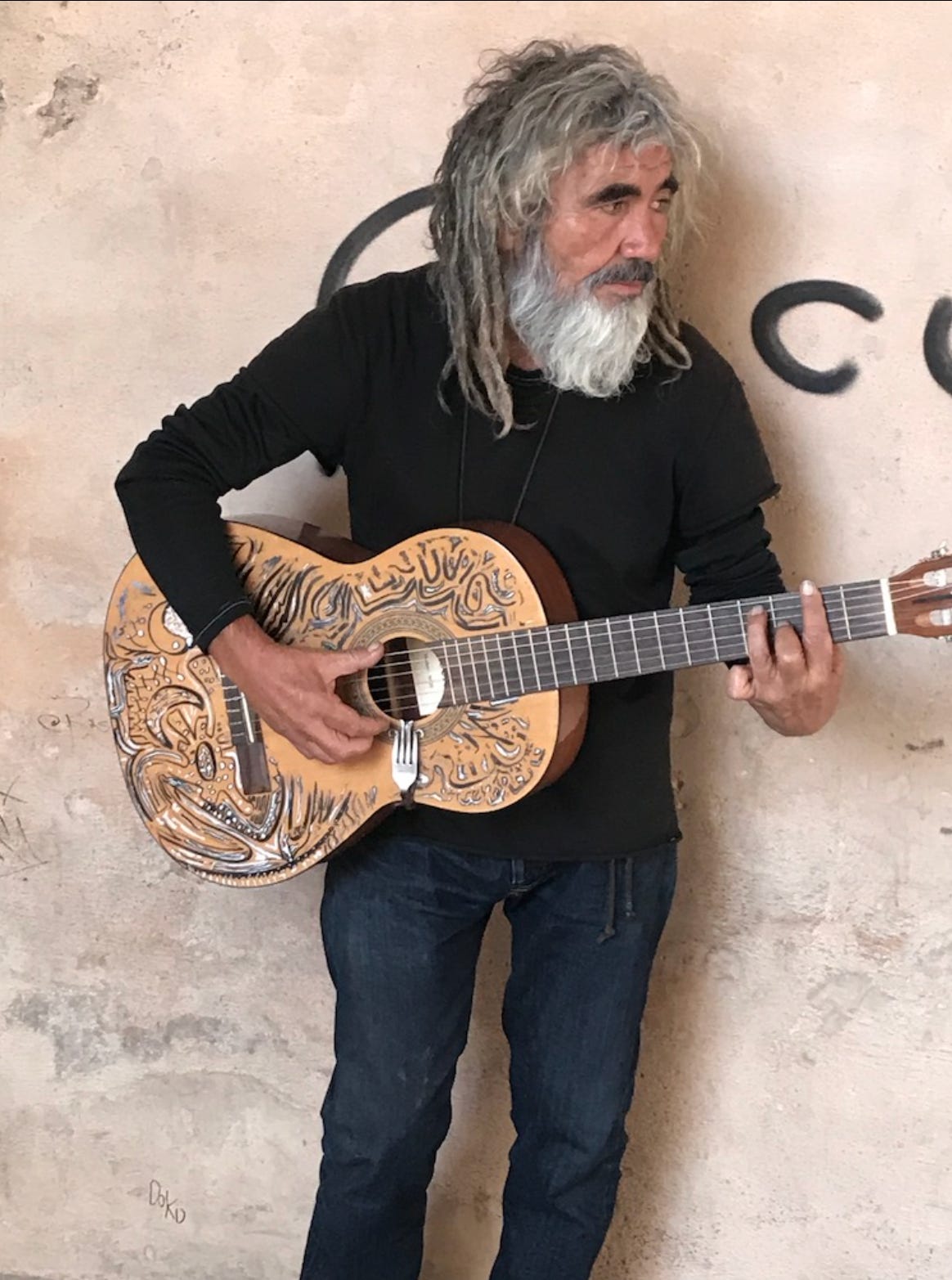

At the age of 65, I am still creating. Certainly not on the level of the artists mentioned; I don’t suggest this at all. But that is not the thing. It’s the creating itself that matters. I have novels waiting to be published, weekly essays to offer, and music to write and produce. This observation takes nothing away from the young who give us the innocence of creativity through untamed enthusiasm at full throttle.

Still . . .

I’ll say it again. I’m 65. Who knew?

There is a glint of morning light coming through the window now, and I suddenly recall the pieces of a particular quote in Siddhartha. I comb the book to see if I might rediscover it, flipping through pages, scanning passages. Minutes pass. And there it is, in Part One, in the section entitled “By The River.”

“After so many years of foolishness, you have once again had an idea, have done something, have heard the bird in your chest singing and have followed it.” —Herman Hesse.

Boomer Power.

To hear one of the songs in the collection of music I’m working on during this chapter of my life, visit Bandcamp.