There’s been a great deal in the news over the last few weeks about the banning of books. We are watching a growing momentum to take some of the classics and award-winning literature off the shelves of school libraries because someone or some group has deemed them inappropriate. But what is really going on here is more than the banning of books, it’s the banning of ideas, as novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen wrote in a recent New York Times opinion piece: “Books are inseparable from ideas, and this is really what is at stake: the struggle over what a child, a reader and a society are allowed to think, to know and to question. A book can open doors and show the possibility of new experiences, even new identities and futures.”

And open us to ideas; ideas that are the seeds of the artistic life. If books are banned along with the ideas they offer, then the artistic process is banned, too. There is no separating one from any other.

Almost a year ago, I was reading in the small shed where I write and work, as cold as it is this morning as it was then. It was a book I had purchased after the death of writer/poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. His novel Little Boy. He called it a “novel,” but it is, for all intents and purposes, a memoir. His final work is a nod to his life, his memories, his influences, the meaning of why we are here—every page filled with wisdom, social and political commentary, ruminations on art and modern technology, and both the beauty and despair of a life lived long and full. He also writes about the mystery of the artistic process and the scourge of censorship. Ferlinghetti knows a few things about that. His City Lights Books has been in the middle of several fights against the banning of books, including the historic censorship battle over Allen Ginsberg’s Howl.

Still, as much as I admired Ferlinghetti, in the first read, I couldn't get through Little Boy. I have loved Ferlinghetti’s poetry, his wit, his steadfastness in creating and sustaining one of the world's greatest bookstores and publishing houses. He had a beard and a bald head like me. People like us stick together. He was a painter, like Henry Miller, whose art I have loved. Painting was something my father did well, a discipline I always had thought would be a wonderful thing to try, but never have. Ferlinghetti was not only a friend of Ginsberg but Kerouac, too, and many of the Beats. He championed art and the avant garde. He had a cool cabin, rundown as it was, in Big Sur. He was a Buddhist. There was a lot to like.

But the book. The book was a struggle, written in Joycean style, little punctuation, one long sentence, nearly. It floats and it wiggles and it meanders. Stream of consciousness, with many difficult-to-follow detours.

The other morning I awoke early from a fitful night of sleep, wild and disjointed dreams. Ideas had come to me at night in a blur, and in the minutes after awakening, I had written a short poem, words fell out of me in a burst. It was both intriguing and mysterious. And there on the round coffee table in our home’s living room was Ferlinghetti’s book where it had been for many months. With the crazy images of my dreams so fresh, that draft of a short poem, and all the recent news about book banning, I was reminded both of Ferlinghetti’s fervor for the importance of art and his intense fight in the long battle against censorship.

I picked up Little Boy and began to read again.

My return to the book was sparked in part by my dreams, meandering dreams of my mother, of snow sledding as a boy, of hiking a Pennsylvania mountain, oddly with a goat. (It was a dream, of course.) I awoke and remembered, fell back to sleep and dreamt more. A train ride in the Alps. Flying over an ocean so blue I could see to the bottom. A dream of my father under his old Pontiac Fury, fixing something, and me, a little boy standing nearby, seeing only his legs and feet protruding from under the chassis. Dreams of my sons. My life, at least part of it had come to me that night in sporadic dreams, bursting and bubbling just below awakening. And then I took pieces of those images and put them down on paper. The spooky art of creation.

I sat in the leather chair near the window and began to re-read Little Boy. I kept reading, Read and read and read. I jumped around the book, stabbing at random pages, and read some more. And it was then that I fell in love with Ferlinghetti's words and his story. It was new. Fresh. Relevant.

Ferlinghetti's book, his novel/memoir is a chaotic ride of reflection, explosions of energy, of light and dark, of quick turns and soft curves, of hills to climb and ones to roll down in laughter, and a middle-finger to those who might ban it. And the book, I realized that morning was exactly what my dreams had been—a series of surges and rushes, exactly what a life is—an unruly, nonlinear narrative, a big box of ideas, made understandable and comprehendible only by the manmade construct of time. Life is one large dream, like Ferlinghetti's book. His "memoir" captures his long life as if it were a dream, full of snaps and sizzles and unexpected turns and twists, of both random deep and silly thoughts, of drama and tragedy, of beauty and loss. We believe and want our lives to be neat and tidy endeavors. They are not. Life is like Ferlinghetti's book, one long unpunctuated sentence bursting with meaning as it flies through the years, from page to page.

Can you imagine anyone wanting to ban those ideas?

It took time and dreams, and the ugliness of censorship to find the stunning and remarkable weight of Ferlinghetti's book, a reminder that life is a frenzied, disordered, untidy mess of a thing. And like our dreams, it too will fade and float into the dark sky of night and the long uncertain blackness of infinity.

No act of book banning can take that away.

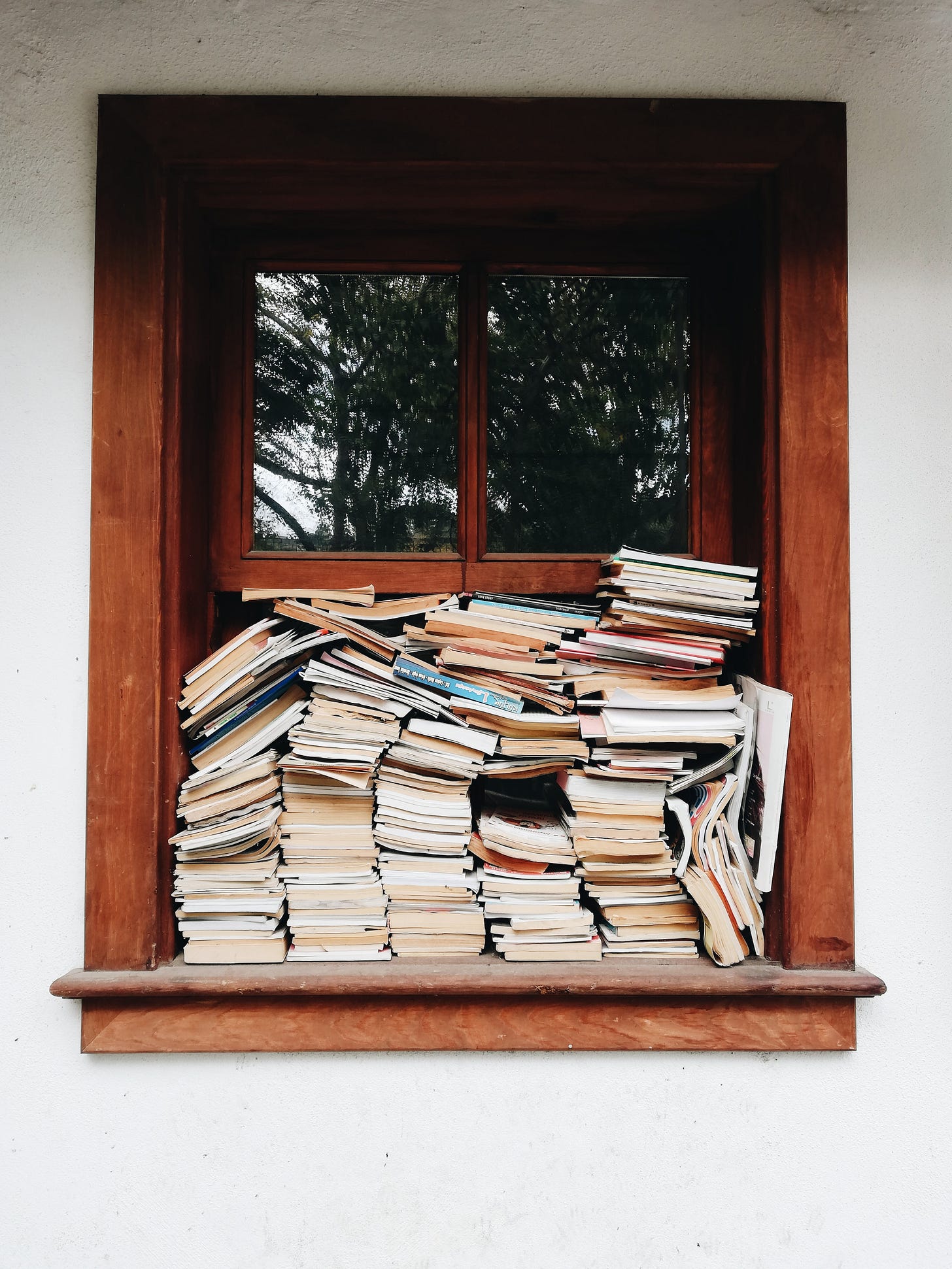

Photo by Zeynep Merve Kılıç Çakır