Mom and the Stolen Stray

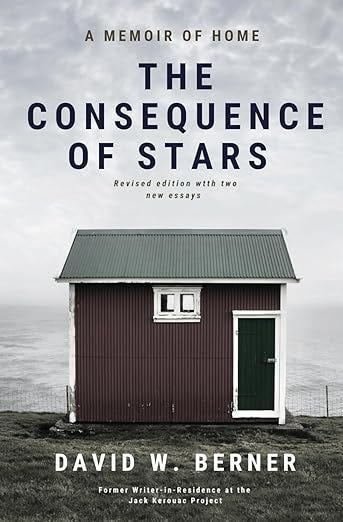

Mother's Day Remembrance: An excerpt from the memoir The Consequence of Stars

This is an excerpt from the essay “The Street Where You Live,” first published in the revised edition of my memoir The Consequence of Stars: A Memoir of Home.

Three strays in one week.

The first was an old tabby cat with a chunk out of its tail. Her father would have none of it, however, and tossed the cat from the second floor back porch over the railing and into the woods. “No damn cats,” he snapped. He tolerated my mother’s love of wayward animals, but he wasn’t about to allow any cats in his home. The second was a scrawny mutt with coarse gray and black hair covering its eyes. Mom’s father fed him some chicken parts in a soup dish on the kitchen floor, but the dog didn’t stick around and was gone the next morning. The third stray appeared to be a mix between a Boston bull terrier and a beagle, a combination doomed for awkwardness.

“He’ll do, if no one claims him,” her father said. “And that’s the only way it goes.”

“What if someone does want him back?” my mother asked.

“Then we give him back. What if it was your dog?”

“But I really like him.”

“He probably has a home somewhere,” her father said, sipping from a can of Duquesne beer, a hometown pilsner made at a brewery near the Monongahela River. “Still, he has no collar and no tag. We’ll see what your mother says.”

Mom stroked the dog’s back as it gnawed at what her father had offered it—chicken gristle and small pieces of fat.

“Hell, he probably hasn’t had anything that good in a long while,” her father said, taking another taste of beer.

My mother was unable to leave animals alone. Any dog or cat left alone on the streets was hers. Collars and tags did not matter. Ownership did not matter. She’d spot the animal on her walk from school, find herself petting it, and soon carrying it or calling it to follow her home. She thought of herself as a pied piper, a rescuer. But mostly it was a selfish act. She once had her own dog, a mix of spaniel and Labrador. Tippy was its name. It died of distemper.

“When he’s done here, put a leash on him, and walk him around the block,” her father insisted. “Let’s see if he’s lost.”

My mother nodded reluctantly. She’d been asked before to do this sort of thing.

Mom put the old leash—one that remained from the Tippy days—around the dog’s neck and twisted the long end through the clasp to secure it.

“Come on, Mickey,” she said.

“You’ve named him already?” her father asked.

My mother walked the dog through the small dining room and living area and out the door to the front porch. She stood on the top of the three cement steps heading toward the sidewalk.

“You got another one?” It was the question my mother remembered Jacqueline, her sister, asking. She was in the yard with a friend, making yellow bouquets from the dandelions in the lawn.

“Yep,” Gloria said.

Jacqueline had been just as much a dognapper as Gloria. One time she hid a beagle mix in the home’s coal cellar. She stuffed food from the dinner table under her shirt and snuck it to the dog until her mother heard its muffled bark. There was an unspoken competition between Gloria and Jacqueline. Which one could rescue the most strays?

“That’s not smart,” Jacqueline said, scolding her. “It’s someone else’s dog, you know? You shouldn’t have it. It’s not yours.” She, my mother thought, was repeating a lesson she had learned after her mother found the beagle.

“Maybe it is,” Gloria said. “Maybe no one wants him.” My mother recalled Jacqueline giggling at this statement.

Mom guided the dog down the steps to the street. When the road dipped and curved, and she was out of Jacqueline’s sight, she abandoned the sidewalk and turned to the woods along a dirt path toward a small stream. She sat behind a large wild cherry tree and held the dog close, eventually pulling it to her lap. My mother stayed there until she heard her father’s sharp whistle, calling her to come home for dinner.

Mom’s mother had made thinly cut pork chops, fried in ketchup and onions in an iron skillet, a frequent dish.

“Can we give him the bones?” Gloria asked. “I don’t see why not,” her mother said.

“Dogs shouldn’t eat pork bones,” her father said. “Too soft. They splinter. They’ll choke.”

“We’ll find him something else,” her mother said.

“Did you walk him along Hazelhurst Street? On Willet Road, too?” her father asked.

My mother nodded.

“No takers?” her father asked. Mom shook her head.

“You sure?”

“Uh huh.”

Jacqueline crossed her arms and leaned back in her chair. My mother recalled her sister’s accusatory words. “She didn’t walk him anywhere,” Jacqueline said. “She sat in the woods the whole time.”

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” her father barked, pounding a fist on the table, his beer can wobbling, nearly tipping over. “What the hell are we going to do with you? Goddamn it!”

Her father stood from the table and pushed back his chair. “Where is the damn dog? I’ll do it myself.” He marched into the kitchen and found the dog resting on a pile of old towels Gloria had fashioned into a bed. Her father huffed, picked up the dog, and carried it in his arms, glaring at my mother. “You just can’t go around stealing dogs.” He snatched the keys to his Jeep from the small table in the entranceway and left, the wooden screen door slapping the doorjamb as he exited.

My mother’s home sat on the knoll where the street dipped down the hill, about a tenth of a mile from my father’s home. It too was brick, but Mom’s home was a two-flat, one floor on top of the other with a small basement. Her English grandmother, her father’s mother, complete with a heavy accent, lived upstairs. On the first floor, Mom shared a small bedroom with her sister. Her parents’ room was next to theirs. Her mother worked part time at the Hilton Hotel in the city, selling cigarettes and cigars. Her father drove a truck for the city’s biggest grocer, Kroger. When the government began rationing during the war, Mom’s father sometimes slipped a few extra pounds of butter in his Jeep. He knocked on neighbors’ doors and left butter boxes on their stoops. He did the same with bags of sugar.

Mom’s father returned without the dog. “It belongs to a family on Churchview Avenue,” he said, walking past his wife to the kitchen. “They don’t deserve him,” he added, opening the refrigerator to grab a beer. “I told them the dog needs to see a vet and that I’d be back for it if they didn’t do something about it.”

“Is it sick?” my mother asked.

“Dog’s got fleas, you saw that. And there’s a sore on its belly. I’m sure you saw that eye? It’s swollen and red,” he said, using an opener on the beer can.

Mom’s mother nodded toward the girls’ bedroom.

When my mother heard the knock on the door, she knew it was her father.

“The dog is back home,” he said, standing at the entrance to the bedroom.

“Okay.” Mom was on her bed, her head in a book. “He seemed happy,” he said.

“I hope so,” Mom said, still not looking up.

Her father paused, placed the open beer can on a tall dresser, and moved closer. He placed a hand under her chin and tilted her head back, so her eyes were on his. “You can’t save them all.”

“Okay,” she said.

“No more,” he said.

“No more, Daddy.”

David W. Berner is the author of several books of award-winning fiction and memoir. His latest, Daylight Saving Time: The power of growing older is available now. His debut poetry collection, Garden Tools is due out in October 2025 from Finishing Line Press. His novella, American Moon will be published by Regal House Publishing in 2026.

This is so sweet.

Is there more?