It was at a yard sale somewhere. That’s where I bought it. Or maybe it was an antique shop someplace. I don’t remember. The portable Royal manual came in its own hard-leather carrying case, the outside stained from someone’s black coffee or spilled wine. When I opened it, the machine’s slim style tricked me into believing it was rather lightweight. It wasn’t—all gray steel and the heft of a big stack of hardback books. And it worked like new. The keys tapped with precision and sprung back like magic. The ribbon was worn but there was enough ink to allow to me type out a few words as a test of its abilities.

i write these words to see if this thing still has it

I bought it for—what was it?—$5?

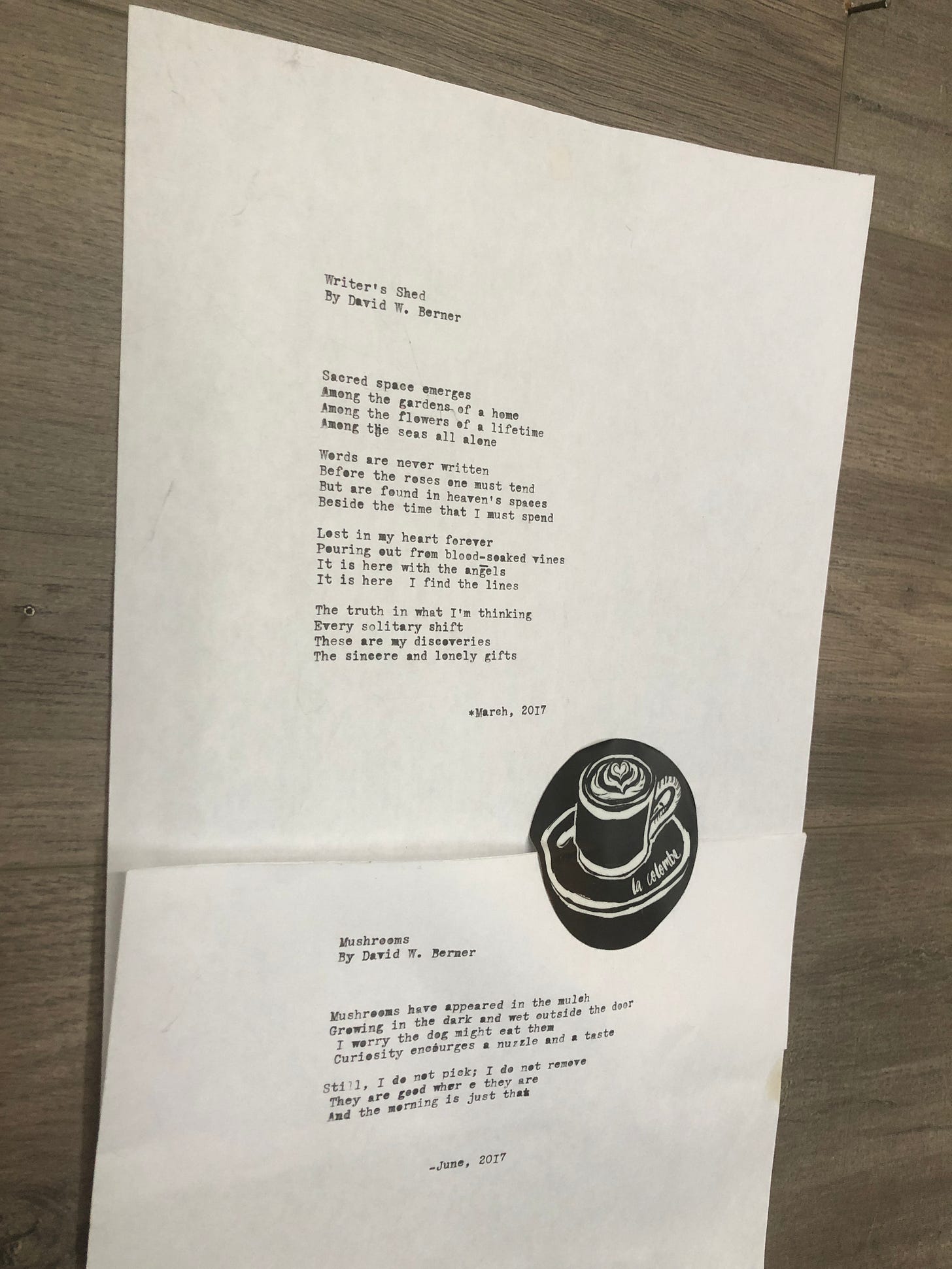

The typewriter has been with me for more than twenty years, and I can’t imagine it not being near, although its keys have produced no more than some 120 of my own words. I’ve written eight books and countless essays and stories. Not one on the Royal, only two short poems that I’ve taped to the wall of my writing shed. Since 2017, when I wrote those poems, the typewriter has sat silent on a shelf behind my desk, as it had for many years before those verses were written.

The typewriter was once one of Royal’s most popular. The Quiet DeLuxe. One of Hemingway’s favorites. The first rendition was manufactured in 1938 and was produced most every year until 1959, with only a short gap during WWII. From what I can gather, my Royal is circa 1940.

I had a couple of other manual typewriters years ago, also Royals. They were from the 1920s, but they didn’t work well and would have required expensive love and care. I sold or gave those away, I can’t recall. But the Quiet DeLuxe remains.

Why do we keep what we keep?

The other day, my wife emailed the link of a year-old Ann Patchett essay from the The New Yorker entitled “How to Practice.” We had been considering a road trip from Chicago to Denver where my wife’s daughter lives to drop off a family treasure, an extensive collection of Wedgewood china—settings for twelve, gravy bowl, the works—purchased by my wife’s father while stationed in England in 1954 during his military years. The plates and saucers became the family’s “good dishes” for decades. Eventually gifted to my wife, she too had had them for many years. Occasionally during the holidays she’d set a formal table, but it was rare. Mostly they remained neatly and securely tucked away in the dark of the basement. Now living in a smaller home, an extensive collection of stuff collected over the years, and a current urge to minimize and simplify, it seemed the time to pass along the china. But shipping would be problematic, expensive, and worrisome. So, the road trip was planned. It was time to pass the china off to the next generation even if it meant driving nearly 1000 miles.

When I consider these kinds of generational gifts, I wonder, as Patchett did in her essay, if we hang onto such things simply to keep our distance from death. My wife says she feels some of this as she packs up the china. But knowing her, she’s likely thinking more about what else she can remove from our shelves, under the bed, and the wayback of the closets, and less about what will happen to those things when she’s no longer here. Still, it’s certain that when we are officially gone, if we haven’t already passed our possessions along to those we love, what remains will likely be offered to the Salvation Army, Goodwill, or sold at a garage sale. The dead need nothing. But if we give away any of it now, it moves us closer to the end. Can we handle that thought as we continue to live? When I’m dead, I won’t need my father’s onyx ring that circles the third finger on my right hand. My son Casey will get that. I won’t be able to strum my old six-string Yamaha acoustic guitar, circa 1972, when my ashes are scattered on a hillside somewhere. My son Graham gets that. Gifting these now would only remind me that I’m closing in on the finish line. So I continue to wear the ring and pick the strings on the guitar.

But what about the typewriter? It is silent. Unused. What happens to it? Who would care to have the old clunky Royal?

I should give it away. It has no function in my everyday life. Someone would have it. My rough calculations prove it’s worth about $100 on the collectors’ market. I should post it on Facebook Marketplace.

But then I remember something else from Patchett’s essay. She, too, had owned typewriters. Ones, she too, had never truly used in her professional, best-selling writing life. Still, letting them go signaled how time was running out. Like me, she couldn’t part with them easily, only to finally give away her favorite, an Olivetti, to a young woman who was infatuated with the old machines and had always imagined herself, the way Patchett had once imagined herself, as “a girl with a typewriter.” It was the symbol of a particular kind of existence, lifestyle, and carried a certain kind of dream.

And that was it.

I had alway imagined myself as the “boy with a typewriter.” That 80-year old Royal represents more than a possession to pass on or give away; it has become something far beyond the crafty old machine that had once produced words, even if they were never my own. Instead, it represents who I was, who I remain, who I want to be—the writer producing the tap-tappity-tap in the early morning hours inside a small shed, the window cracked open, hot coffee in a mug, the sun’s early light glinting off the fence post just beyond my view. That typewriter is how I see me, and what I have dreamed myself to be.

I will continue to work on my laptop, as there are no plans to place the Royal on my desk and write. But there will always be a place for it on the shelf where it sits, and when I’m dead, someone else can decide who keeps it or gives it away.

Nice essay. Do I get my copy of Writer Shed 3 soon?. I hope so.