Not long ago, I rediscovered some of my father’s drawings, ones he had produced as a boy. Pencil and charcoal drawings on simple manila sketch paper which had crumpled and decayed over the many years, becoming frayed and fragile.

The drawings had been inside a file folder I’d inherited more than a decade ago. I knew I had them. But for whatever reason, they stayed in that folder. I guess I thought it was a way to preserve the work. Or maybe I was subconsciously adhering to what I thought were my father’s wishes—to keep his art to himself.

I was introduced to my father’s artistic side when I was a young boy. He would sometimes sketch little scenes on napkins at the end of Sunday dinner. He’d draw men sitting at bars, smoking, drinking, laughing. He’d sketch a dog or a cat. A boy fishing along a lake.

“Draw something else, Dad,” I’d say, anticipating his next creation, fascinated by his magic. And I believed it was exactly that. Magic. How could he do such a thing so effortlessly?

As a young boy, when my parents would go out on a Friday evening, I was sent to my grandmother’s house down the street for the night. Upstairs in the old house in the bedroom that had once been my father’s room, there were pencil sketches adorning the walls, drawings on the plaster and paint. At first, I didn’t think much about them, too young to understand their significance to my father’s early years with art. For many years, my grandmother painted around the sketches when she freshened up the decor in the room, leaving them intact, the paint’s edges forming a kind of border around my father’s boyhood work.

One day, when I began to wonder about the drawings, I asked my grandmother, “Did Dad draw all of these?”

“Yes, he did,” she said. “Each one.”

The sketches were of pheasants in flight. Deer. Hunters walking the woods. Ducks on a pond with cattails at the water’s edge. Outdoor scenes by a boy who had grown up in the forested hills outside Pittsburgh where hunting and fishing were a way of life. My dad likely drew those scenes when he was about ten or eleven years old, certain to keep his art closeted in his dimly lit bedroom. For decades after, my grandmother couldn’t imagine ever painting over the drawings.

Years later when I looked at them with a bit more knowledge of Dad’s work, I imagined my father as an auburn-haired little boy, finding solace and beauty in his natural and innate ability, a way of escaping from the world that would soon include the coming break-up of his parents’ marriage. His mother saw something special in her son’s ability, but maybe didn’t understand it. What would he do with such a skill in a city of steelworkers and bricklayers? How could artistic talent amount to anything more than what his father had seen as a silly hobby, a boyhood distraction that wasn’t important to a child’s development from a boy to a man?

When my father got his first job at the age of seventeen—a carpenter on a crew building house—he wasn’t sketching much anymore. When he was drafted into the Army and soon after married my mother, he produced hardly any art at all. And when he became a father, his days of sketching were far behind him. Later in life, he picked it up again, but the passion was never quite the same. One could see that the act of living had squeezed it out of him. He had obligations and responsibilities. As a middle-aged man, he would again draw now and then on a Sunday dinner napkin. And when my boys, his grandsons would come to visit, he would fascinate them with a sketch or two. “Pappy,” they’d ask excitedly, “draw something else?”

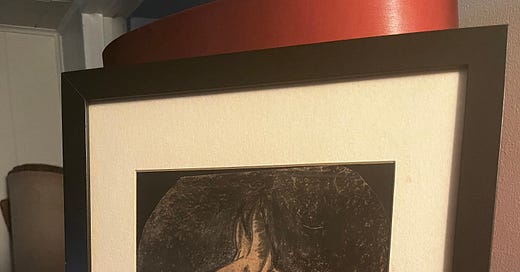

Inside the old file folder were sketches of Billy Conn, the famous boxer, of dogs, and babies, and birds. Sketches he never shared; hidden art seen by few. Like the sketches on the walls of his boyhood bedroom, my father’s artwork was held close, as if it were nearly unbearable to share, a measure of vulnerability my father didn’t appear to want to face.

I’ve given two of Dad’s drawings to my sons, one each. Several others are now on the walls of my home. I appreciate them more than ever, and I wonder what my father would think if he were still alive. How would he feel about what I’ve done with this art, how I’ve carefully and delicately placed those seventy-year-old sketches in frames and displayed them for all to see? I wonder, too, about anyone who creates art or writes or sings who may be too self-conscious to share any of it with the world, whose skill has been diminished by criticism or dismal, closeted by vulnerability.

The final act of any creative endeavor is to share it, to give it to the world. Music producer Rick Rubin writes about this in his wonderful book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being: “One of the greatest rewards of making art is our ability to share it. Even if there is no audience to receive it. Despite our insecurities, the more times we can bring ourselves to release our work, the less weight insecurity has.”

I’m sure all those years of not sharing his artwork only compounded the insecurities my father undoubtedly had as a boy, a boy who found a little touch of happiness in the reclusive act of holding a pencil in his hand and drawing what he imagined in his head, recreating it on the walls of his bedroom.

Now, with some of that art on the walls of my home, maybe Dad is finally feeling like the artist he’d always been.

David W. Berner is the author of several award-winning books of fiction and memoir. His book Daylight Saving Time: The Power of Growing Older is now available for pre-order.

What a beautiful essay! It makes me smile and now I want to go look at the wood carvings I have by my dad that he made in his retirement. Thank you for sharing your art!

I just love that your grandmother painted around the drawings your dad did on his bedroom walls. That is something I would definitely do!