We were in a pub down the lane from Wroxton Abbey in Oxfordshire. He had asked me to lunch. Why me? I had wondered. There were over a dozen writers staying at the abbey as part of the Fairleigh Dickinson MFA program in England, all of them looking for his direction. Why did he want to eat shepherd’s pie and drink a pint, or two, with me on a cool January day when he could be doing, I don’t know, something more interesting?

Thomas E. Kennedy’s smile was inviting. When I met him the first time, this was what left the biggest impression. It was genuine and gentle. But it was his natural curiosity and his intellect that stayed with me after getting to know him better. He was sharp, witty, and always completely present with whomever he was spending time. He had been assigned as my advisor/mentor for the program, an acclaimed ex-pat writer who could recite long stretches of James Joyce and Dylan Thomas, talk to you for hours about how literature can change the world or about the subtleties of a great vodka. I found him not only warm and welcoming, but utterly fascinating, a writer’s writer, a brilliant scholarly man who could also tell a great bawdy joke. He was born in Queens, NY in 1944 and as a young man had hitchhiked across America. In time he found himself overseas, becoming a citizen of Copenhagen, his adopted home. Tom still had a bit of his New York accent even into his later years, but his nature, his sensitivity was purely European.

Before coming to FDU for the program, I had read some of Tom’s work. I was knocked out. He had perfect rhythm in his writing, keen observations tinged with philosophy, and an uncanny understanding of the complexities of humans. Although his fiction and short stories were stunning, it was his creative nonfiction that truly gripped me. I recall a piece he wrote for Pif Magazine about his father, writing, and New York City that had intimidated me. It was so good!

Why would this extraordinary man of words ask a green and uncertain new writer like me to lunch?

Here is how I remember that afternoon.

“So what do you think your themes are?” Tom asked as the server dropped two pints in front of us.

“Hell, I don’t know yet, really.”

“From what I’ve read so far,” Tom said, “it’s about fathers and sons, don’t you think?” He took a long gulp of his Guinness.

Tom had read my manuscript-in-progress at the time, the work that would eventually become my first book, Accidental Lessons. What I didn’t know was how very closely he had read it.

“Well, yes,” I thought aloud, “there’s that.”

I remembered Tom’s piece in Pif. Tom had written about his father wanting to be a writer, about him once publishing a poem in the New York Times, and how Tom had also tried to be a writer, using his father’s Remington manual typewriter for more than fifteen years without a single word being published. “I had to leave the city, get out of the country, to write anything worth publishing,” he wrote.

Now, like Tom, here I was, out of my country, trying to find out how to make sense out of my own sentences.

“Are you working on anything else?” Tom continued.

I smiled. It was if he already knew.

“Funny you ask.” I smiled again, shaking my head with disbelief. “I’ve been playing around with some essays about fathers and sons.”

“Not surprising,” Tom said. He offered his pint glass to mine, smiled, and clinked my glass.

“That’s a little scary, you know?” I said.

Tom laughed and winked. He was teaching me.

“You’ve written about your father,” I said.

“He was a complicated man. A bit of a riff in the family over my writing about him. It isn’t pretty.”

Tom sat his pint down and looked beyond me out the window to the lane. He paused then turned his eyes toward me again. “You have to write your truth,” he said. “It’s yours. Be true to that.”

Those words were my most important lesson during those days at Wroxton. Tom’s simple thoughts about truth. He would later help me with scene development and sensory language and a slew of so many things, but those simple words in a quiet English pub on a gray winter day were golden.

A few days later, Tom would ask me to join him and another professor/writer on their annual hike around Oxfordshire, a long country journey over green hills and through tiny hamlets of thatched-roof homes. The day ended at a pub with a pint and a cigar. It is one of my fondest memories. A few years later after I had completed my MFA and had returned to America and Tom had gone home to Copenhagen, a Chicago publisher released my book about fathers and sons, Any Road Will Take You There. It won a Chicago Writers Association award.

For a few years after those days at the abbey, Tom and I kept in touch. He came to Chicago not long after Wroxton for a seminar and a talk at Harper College. I joined him for lunch afterward. He asked about the progress on the publication of my first book, the one he helped shape, the one for which he had so graciously offered to write a blurb for the back cover. The publisher’s editor and I had had our differences over where the commas should go, I told him. He laughed. That smile so apparent.

In October 2021, I had been conducting an online writing workshop, and one of my students was from Copenhagen. “I have a wonderful old writer friend there,” I said. “Thomas E. Kennedy. Have you read him?” She had not heard of Tom. I told her to be sure to read his work. “He’s a genius,” I said. The next day, I found Tom’s email in my contacts and sent him a note. It had been years, and I had been terribly remiss in staying connected.

I never heard back.

What I didn’t know at the time and discovered just a few days ago was that Tom had been dead for some five months. He had passed quietly in his sleep at his home in Denmark at the age of 79.

Tom dead. How in the world did I miss this? How did I not know? My heart was full of sorrow, guilt, longing. I searched the internet for an obit, found one, and also discovered that his colleagues had published a book as a tribute: Celebrating Thomas E. Kennedy. I bought a copy. Searching my old emails, I found a correspondence from 2014 that I’d had with the other professor at FDU who had joined us on the long walk in Oxfordshire. In the thread he had mentioned that he’d had photos of that hike, some pictures of me and Tom together. Goodness, I hope he still has them. I rushed off an email, telling him how I had just learned of Tom’s passing, that I was shocked and remorseful for not being aware of his death, of not keeping in touch, of letting the knowledge of how influential and important Tom was to my writing life slip away over the years.

I’m still waiting for a reply.

Regret is a strange thing. Some say we should never succumb to it. But I think regret, in many ways can be good. It’s how we learn about ourselves, about what is important, about what we really want. Regret can offer clarity. And it can help us see where we have lost our way and then how to return to the our path.

I regret not staying more closely in touch with Tom. There are few if any people who in such a short period of time have meant so much to my creative life. Still, I am grateful that the memories will alway be there, and that my writing will forever have a little of Tom in it.

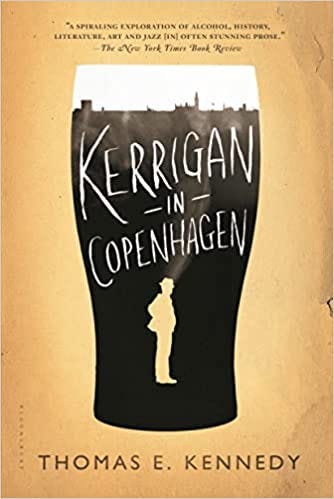

Photo of Thomas E. Kennedy: Books&Books