The other day, I found something, something I had thought lost.

During a surge in “readying-up” the house—an old Scottish phrase that suggests one is cleaning, straightening things, and throwing out what is no longer needed; and as my head was digesting paragraphs I had written that morning for a story I was working on—I rediscovered an old photograph in a nightstand drawer, a forgotten image, a photo I thought had been long gone. It is a black-and-white of my father as a young man, a U.S. Army private, wearing a white tee shirt, an apron, and cook’s cap. He had been a cook in the Army and in the photo he is holding a big rolling pin over his head inside the kitchen of a mess hall as another Army private clutches a large cooking pot for protection. A third looks on, cowering. It is a staged photograph, a playful one—the men with big smiles, the men so young.

I love that photo. My father had a great smile. He was a great storyteller. A good man. And that old photo captures so much of him, the young man who would not be a father for a few more years, the young man not yet married to my mother. The loss of that photo would have saddened me. But as I held it in my hand that afternoon, I realized I had never really lost it in the first place. It had been buried in the drawer and never truly been missing. But even if it had, the image of my father in that photo had always been and always would be with me.

I am a loser of things. Car keys. Wallet. A misplacer is probably a better way to describe my mild affliction. I’ve been temporarily losing things since I was a boy. My mother used to call me the Absent-Minded Professor, and I am quite aware of why that name fit then and why it does now.

My mind is a busy place. I am forever exploring, rearranging, and dreaming. That may sound wonderful, but it isn’t always. Being present, as the Zen masters say, is a state of being I have not yet perfected, although I often try. A good walk helps. But my busy mind usually wins. And so, I lose the pair of glasses I had removed inside a bookstore, and the wristwatch I’d taken off before playing baseball in a grassy field. The lost and the misplaced have always bedeviled me.

After my parents died, my sister lived in their old house for many years. When it came time for her to leave, in that process, a large box of photographs was lost—photos of grandparents, great grandparents, family vacations, and an entire folder of photos my mother and father had taken when they visited England in the late 1970s, a trip my mother had only dreamed of taking. On the long flight to London, she held in her hand the handwritten address of her father’s childhood home on the Isle of Wight, the home she had vowed to find and eventually would. That trip meant so much and those photos so precious. But like the old Army photograph of my father, the images of that trip may have been physically lost, but were not gone. They had been there in my mind’s eye.

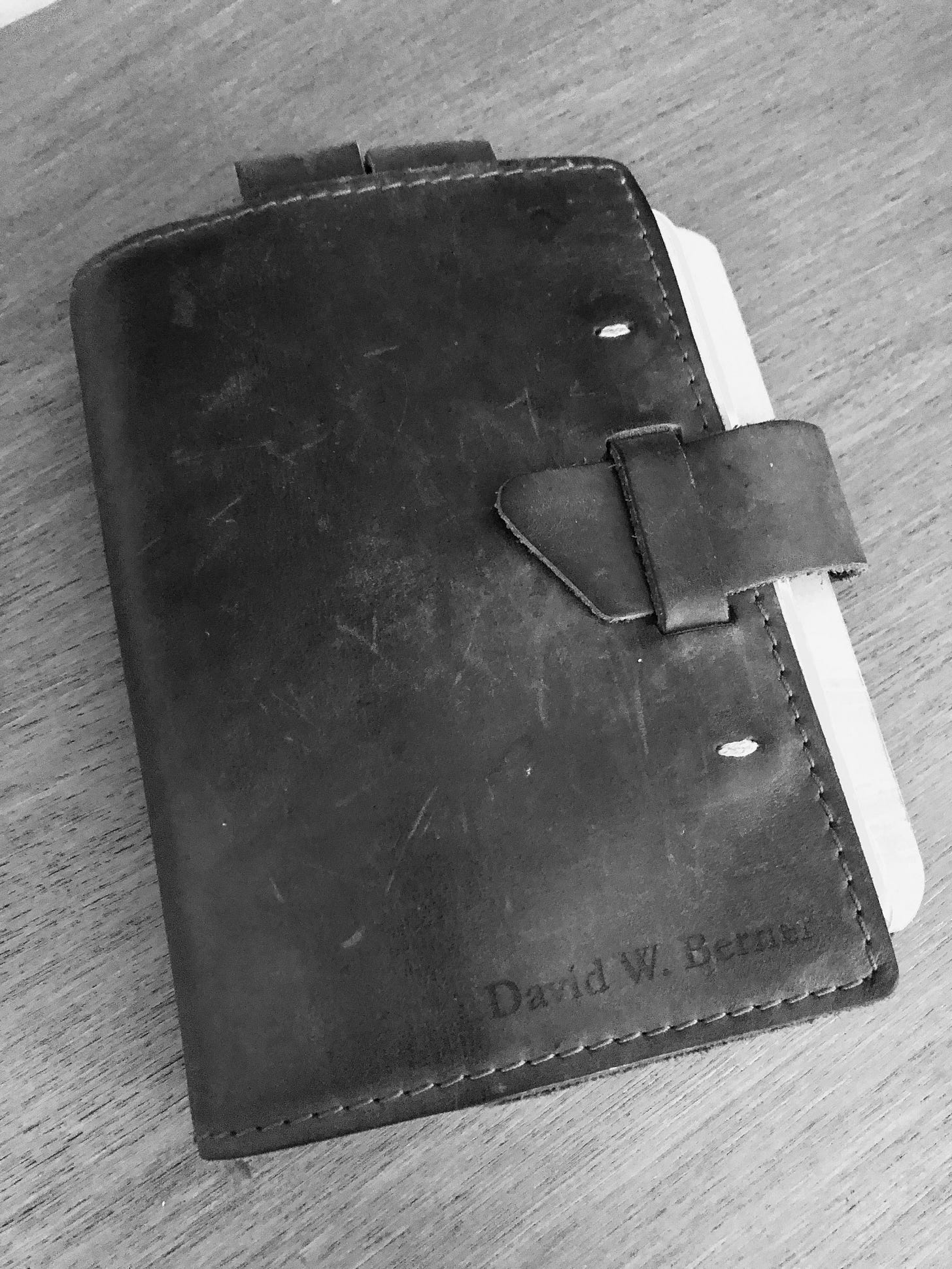

I have a leather journal where I write thoughts, ideas, poems, scattered dreams. I have several notebooks, but that journal is the one that has most of my attention. It’s not a diary, and its entries are not meant to be a chore, an obligation, or a daily event. Instead the journal is a place to capture what I am frightened I may lose. If I don’t write it down, it may vanish. But I wonder, would I really lose it? Instead, it is the fear of losing it that compels me to use pen on those pages. And as for all those photos, were they taken only to capture what we were afraid might vanish? Still, neither my journal notes nor the old photos are ever truly lost. And as I grow older and memory fails me, I promise myself I will not spend my days looking for lost things because memories never fade completely, they are always there—maybe battered, maybe broken, maybe just out of our grasp as the mind struggles to hold on to what is real—but they remain in some way even if only in foggy corners of the heart.

The body, sluggish, aged, cold—the embers left from earlier fires, the light in the eye grown dim, shall duly flame again.

The words of Walt Whitman hold true.

I smiled for a long time, looking at that rediscovered photo of my father and the innocence in his young eyes. And I wondered what he would think of it today, if he would see the light that shall duly flame again.

Before returning it to a more secure spot in the nightstand, I clicked a photo of the old image with my phone, a digital document to store away. Just in case.

I like his winsome smile.

I'll be sharing this with David Hoffman Filmmaker, who collects old photographs; many without stories. He will be having a birthday soon. This is the perfect gift. Thank you, Mr. Berner.