The Writing House

A gift to myself

As many of you know, I write inside a 8x10 shed on my property. Today, I’m thinking a great deal about this small space that I’ve given myself, a gift to my psyche and my creative side. Do you have a place for yourself, some corner for refuge, for respite, for solace, for wonder? If not, I urge you to create a “room of one’s own,” as Virginia Woolf called it. Make it yours. Write. Play. Dance. Stretch. Dream.

I wrote this essay a few years ago when I moved into the shed for the first time. Maybe it will inspire you to find that “room of your own.”

***

The Writing House

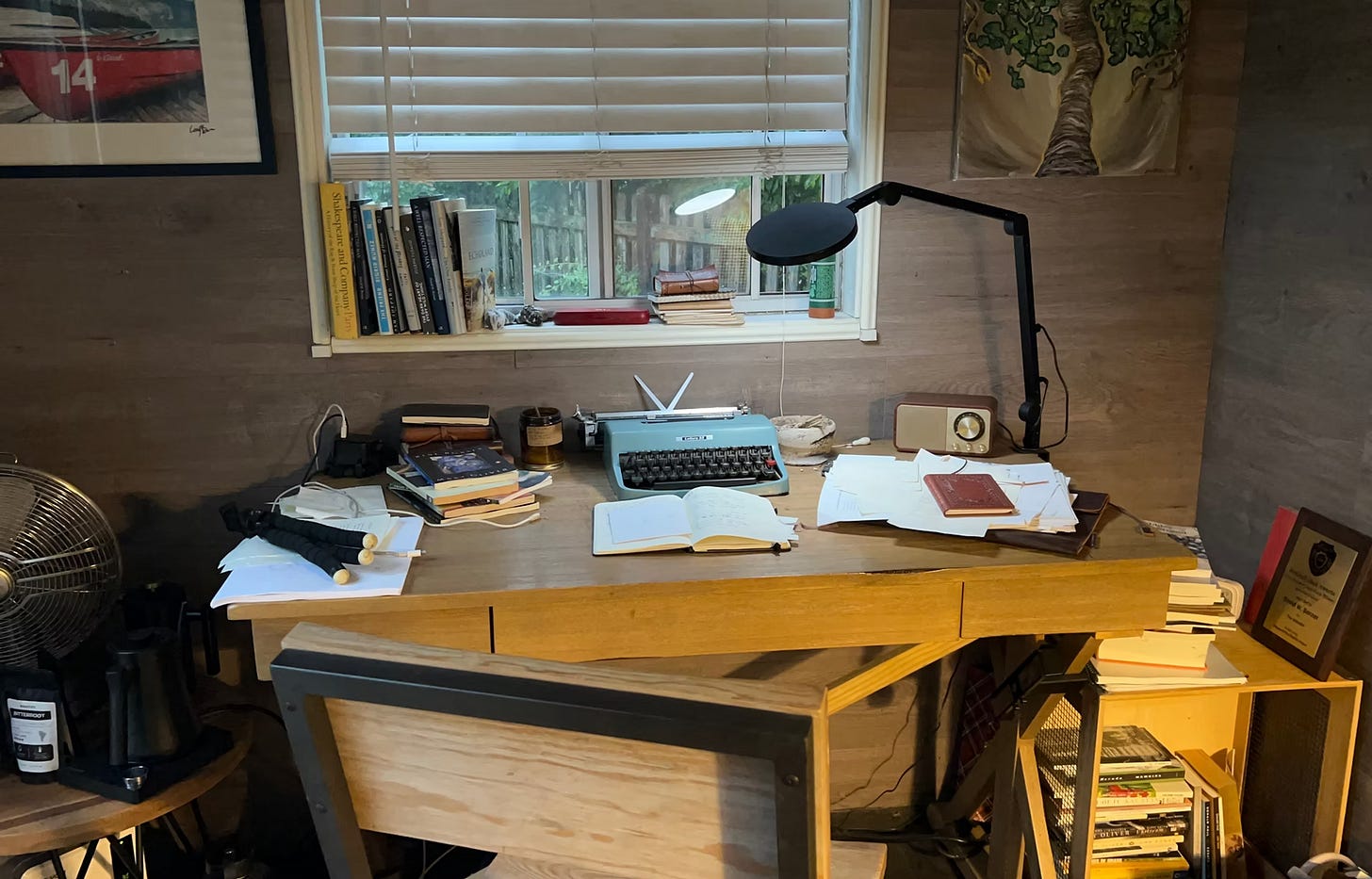

It was one day after carrying everything through the door. I sat inside my small studio—a shed in the backyard—in the quiet dusk of a Saturday among the books, photography, and art. I waited. What happens now? After months of filling out forms for a village permit, hauling in the shed’s framework on a flatbed to the corner of our plot of property, breaking numerous jigsaw blades, nailing barn wood panels to studs, painting the ceiling, and squaring up a vinyl floor, I anticipated some magic.

I had dreamed of this day for a long time, even though at times I questioned it. You’re going to build a writer’s shed? You’re going to be some Henry David Thoreau wannabe? There were those who simply smiled when I explained the not yet fully formulated plans. I’m sure some turned away to laugh. But the dream was real. And after the last of the vinyl tile was glued to the subfloor, I was proud, satisfied, and weary—a good weary, the kind that comes after physical accomplishment. There was soreness in my right hand from wielding a hammer—I probably was using it incorrectly—a bruise on my thumb from a misguided attempt at using a screwdriver to remove a bent finishing nail, tight back muscles from climbing up and down the ladder, and aches in my hips and thighs from squatting and stretching to meet the highest and lowest corners of the 8x10 space. There also had been outbursts, cursing miscalculated measurements. Despite the minor bang-ups and pains, there was joy. In each step of the work, I could see and feel the writer’s shed—a place of my own—emerging. I saw myself stealing away inside in early mornings to read and write. I was Thoreau. I was Dylan Thomas in his boathouse in Wales. I was Henry Miller in Clichy, his artistic home. Still, looking back at this process—the planning and then building out the interior of this writer’s home—I was clearly in fantasy mode. I imagined the glow of creative solace. But there I was, alone, at my desk, with evening’s full darkness closing in outside, void of romance. Reality was here, and now the mysteries would begin. Can I write here? Have I built this space only on a dream of what it might be? Have I erected my writer shed only to seduce a distorted image of artistic solitude? Have I miscalculated the value of this space, this home?

The reality of the shed formed after meeting Leslie, falling in love, and moving to her home together after living alone in a two-flat near Chicago. After nearly two years, I asked, “Would you let me build a writer’s shed?” The new home was the first place I had lived where the vision of a shed felt truly possible. Leslie gave it her blessing, even encouraged it. But then there was anxiety. It was not unlike what one experiences on the first night in a new apartment or new house. You are awkward and uncertain. Did I make the right move? Your mind can’t be settled. You can’t sleep. You are out of place, out of sync with the dream, not to mention the apprehension of being secluded with your own thoughts. I have always considered myself someone who savored solitude, believed in its restorative power. The shed is not a cabin in the wilderness, but it is isolation nonetheless. Still, I may have underestimated what surrounded me.

I turned on the chrome lamp at my desk and looked for a book on the small shelf in the corner near the door. Gretel Ehrlich in The Solace of Open Spaces focuses on the American West, the vast openness she needed during a particularly tough time in her life. I love this book. I read aloud a passage I had marked with a pen long ago: “We fill up space as if it were a pie shell.” I wondered if I had filled up too much. Ehrlich writes how taking away space “obstructs our ability to see what is already there.” Did I construct this writer shed on my “space” to obstruct my view? Did building it cloud my vision? Is the shed a facade for the real work of writing? Is the shed only a place to hide?

Building a house in America is the work of ego. Make it big. Make it bold. Fill up the space with rooms, more than you need. No finished basement? That won’t do. No master bath with walk-in shower? Unacceptable. What do you mean it’s only a one-car garage? These perceived needs obstruct the view of a house’s true and elementary purpose—to shelter and, more importantly, to nurture. The shed will shelter. There are no leaks in the roof. But I pray it will nurture, allow space for quieting the mind and soul. The shed was not built out of ego or status and certainly not simple shelter. It was built in an effort to comfort something deeper.

When first filling the space inside, I placed on my desk, a gift from Leslie—a small framed watercolor of Dylan Thomas’ desk in his writing shed inside the boathouse and garage along the rocks in Laugharne, Wales. Also depicted in the painting are pen and ink, journals, and scattered papers. The view is Thomas’ view, out the window to the Taf Estuary and Gower Peninsula. This painting and all the photos I have seen of the poet’s shed show the curtains open to the countryside, natural light pouring in. My view is north toward the wooden fence and the neighbor’s back lawn. At night when the sun is long gone, I can see mostly misshapen shadows—blacks and grays. Only a small, soft light shines from a neighbor’s patio and filters through a large pine at the border of the property, reflecting off the window and into my shed. It’s not enough to create a silhouette or warm the room, but it soothes nonetheless. There is no estuary or peninsula, but there is open space of a certain level, and I have given it permission to come inside.

I recently wrote a short piece about the world’s most remote places. The shed and home in Laugharne were certainly not remote, not when compared to the world’s most inaccessible places, or the vastness of what Ehrlich wrote about. Dylan’s boathouse was walking distance from town, Browns hotel, and an afternoon of pints. But when inside his writing space, he was long gone. Tristan de Cunha is the most out-of-the-way inhabited archipelago in the world. It sits 1700 miles from the nearest island in South Africa. My shed is 100 feet from the back door of the house. I can see the garage from the window. Yet somehow I am distant, just on the edge of aloneness.

On the shelf to my left, I’ve placed a copy of Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Peak. Big swaths of the book are taken directly from Kerouac’s journal while he was a fire lookout in a cabin in the North Cascades of Washington state in the summer of 1956. For two months he was isolated on the mountain. The book is a study in seclusion, Kerouac’s opportunity to be silent, to think, to write in isolation. Desolation Peak was his Walden. Just above Kerouac’s book on the same shelf is Thoreau’s book. A few weeks ago, I reread Walden, compelled to as I sawed and nailed my way through afternoons. The first time I read it, I was a high school freshman. I believe I read only parts of it. Back then I saw Thoreau only as a nagging assignment, an old 19th century recluse who wrote silly nature stories. Things changed, of course. On my second go at it, I opened Walden and thumbed through. I read a passage on a dog-eared page: “I never found a companion that was so companionable as solitude.” The words stung a bit. Is my shed a place for the hermit in me? Am I only longing to be a recluse? I leaned back in the chair and looked around. On the desk is a framed photograph of a remote boat launch in Canada. The rowboats are red and numbered. In the background are craggy mountains, fog and snow. My son, Casey took the photo. I wanted it in the shed. It speaks to the inner human need for solitude. But so many other things inside offer other things, different sides of me. On the bookshelf is a small bowl, handmade with clay and horsehair. My younger son, Graham crafted it. Tacked to the wall is a pencil drawing, flowers in a vase, the artwork of my partner’s daughter, Jen. The watercolor of Thomas’ shed is next to a small card with a hand-printed, two-stanza poem. “From the Sky” is the work of Gary Snyder. He graciously signed it for me after I attended a reading he gave in Chicago. And there are the books scattered about—Jim Harrison and Joan Didion and Walt Whitman and Karl Ove Knausgaard. Not a lot of them, only the ones I most cherish, the ones that give me peace. I am surrounded and I am not alone, not a loner. I have created a kind of home inside these walls, a home for seclusion, yes, but also, maybe more importantly, one of shared art and love, the opposite of isolation.

Still, there are pieces missing.

I looked around again—on the desk, the shelves, in the drawer of my desk. There is nothing of my sister, nothing of my mother or father. I looked at my right hand. On the third finger I wear Dad’s ring, a small diamond on onyx surrounded by gold, the ring my mother gave him when they married, the one he would never take off, that left a red indentation on his thick finger and now is making the same mark on mine. I would not have purchased such a ring for myself, but I wear it. Still, there is nothing of Dad’s artwork on the shed walls, no pencil or chalk drawings. They are on the walls of the new home but not here, not in the shed, not in this place of creativity. And what about my mother? In the house, in the bottom drawer of my nightstand, is my mother’s engagement ring—small diamond, platinum band, geometric metalwork. It is kept in a mustard-colored felt ring box, the box that once carried my high school graduation ring. Maybe one of my sons will use the ring for the one he loves. And under the nightstand is a hard plastic box. Inside are my sister’s ashes, what’s left of what has not been scattered at a football stadium and a graveyard. Should these things be in my shed? Or am I deliberately keeping them at a distance?

Before finding myself in the shed one evening, I read a New York Times article about the passing of Lou Reed. Laurie Anderson, Reed’s partner in life, was donating Reed’s extensive archives to the New York Public Library. She didn’t want a university to have it. She thought academia would be less democratic, making it less available for those who wished to explore. Reed had left behind hundreds of recordings, notes, receipts, letters, writings, and photographs, all the things that make up an artistic life. But Anderson was saddened that despite all these meaningful remnants, the one thing that may have been most special to Reed was not there in that trove. Reed had a lifelong dedication to meditation. It weaved through his existence. It was important to him. But in all those boxes and folders, there was nothing to be found. No trace of this part of his life. What may have brought Lou Reed his most meaningful peace had vanished after his death. For Reed, meditation, it seemed, was like going home. It was where he felt the most at ease, the most real, but in the end there was no physical footprint that this cornerstone of his life ever existed.

I looked around again at all that I’ve brought to the shed and for what is missing. Is this all of me? Is this it? If these things were my archives, would they say everything about me? Would it matter? Who would care? My life will not be documented at a university or the New York Public Library, but we all want to believe that what we have done with our lives, in some way, will remain after we die. Still, so much of life, of who we really are, cannot be truly captured. It is only in our minds, stays there, and dies there. Sometimes you cannot embrace the most cherished possessions or hold on to the most important things. And maybe that’s okay. There’s beauty in that. It’s the splendor of existence. My father and mother are gone, their true spirit gone with them. My sister—whose end came alone in a hospital emergency room bed, her body ravaged by alcohol—is a heartbreaking memory. But, so much about their lives, despite all that they meant to me, is slowly being lost in the fog of time, visible only when I’m able to fight through the haze.

I hope what happens in this shed will be captured somehow, but the truth is, much of it—like life—will be ephemeral, dissipating smoke. It is true about everything, the people we love and all the places we live, all the homes we embrace. We infinitely search for peace, for home, but the physical buildings that shelter our lives ultimately serve only as greenhouses of our being. Inside them we grow, we bloom, and soon decay and evaporate into earth and air, along with so many of those important moments—difficult and beautiful—that cannot be framed and hung on a wall, or placed on a bookshelf, or archived for all to examine. I didn’t know my sister would die before I would see her one last time. I didn’t know my father loved my mother so deeply until he fought so hard to live. I didn’t know my mother, only in her late teens when fighting tuberculosis, was brave enough to spit at death. I didn’t know my hometown was such a good place until I left it. I didn’t know I would find real love again.

I stood from my desk, took a deep breath, and collected the shed’s keys from the front pocket of my jeans. I turned off the lamp. I reached to close the window blind where the neighbor’s light remained, but I thought again and chose to keep it open. The light was dreamlike, reassuring, like a candle or lantern showing the way. It was magical. And my shed, like all the places called home, could use a little touch of magic.

David W. Berner is the author of several books of award-winning fiction and memoir. His poetry collection, Garden Tools from Finishing Line Press is now available. His novella, American Moon will be published by Regal House Publishing in the fall of 2026.

I have this lovely little building sitting out behind my house the truly needs to be made into something. Maybe a writing house.

You've captured "life" in this essay. Beautiful. Thank you.

"...the physical buildings that shelter our lives ultimately serve only as greenhouses of our being. Inside them we grow, we bloom, and soon decay and evaporate into earth and air, along with so many of those important moments—difficult and beautiful—that cannot be framed and hung on a wall, or placed on a bookshelf, or archived for all to examine."